Pharmakon #10 - Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit - Introduction - reflexivity and commonality

catching the wisp

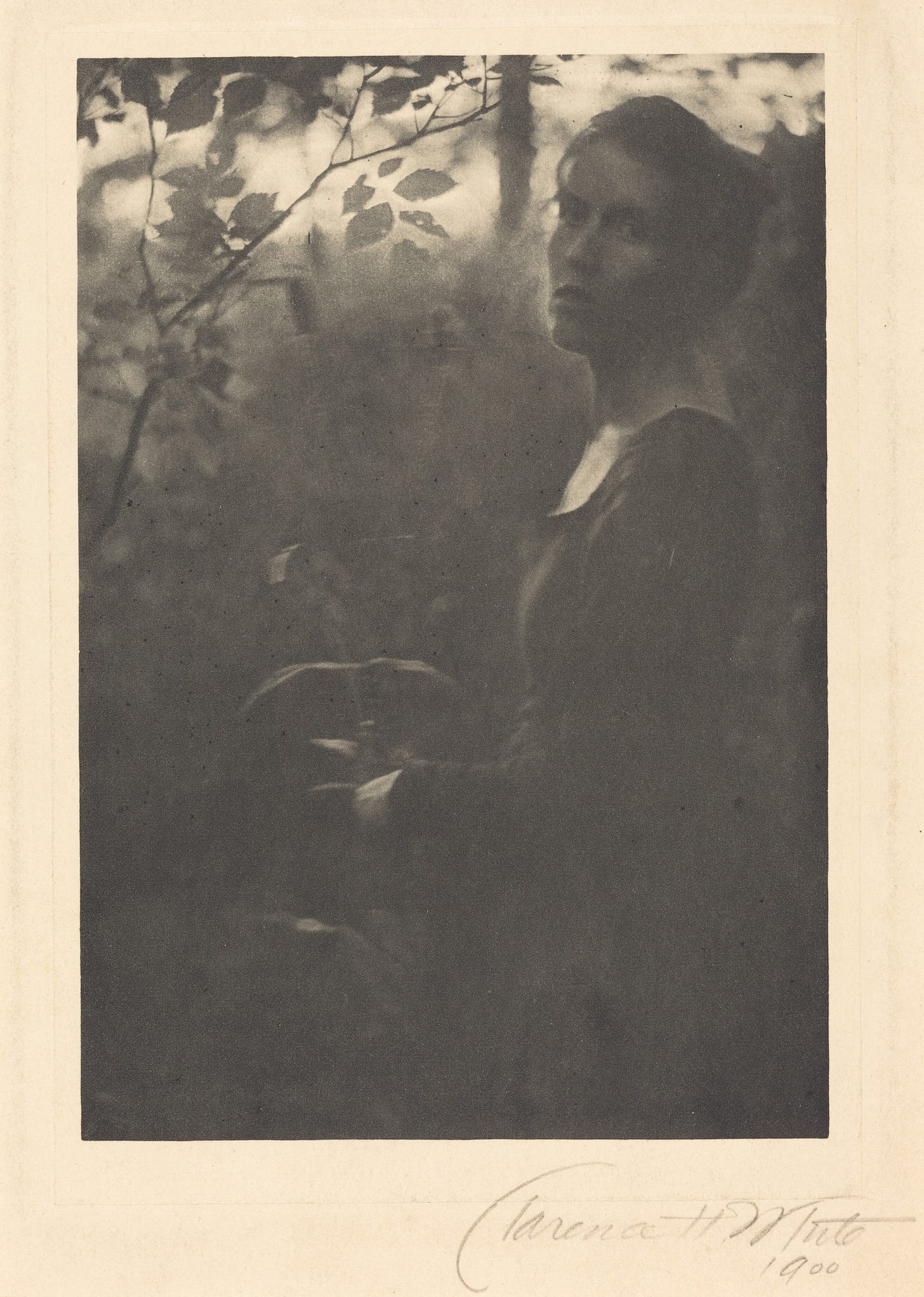

Clarence H. White, Edge of the Woods, Evening, 1900, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit can be found here.

Now, because this account has merely phenomenal knowledge for its object, it does not seem itself to be the science that is free and self-moving within its own distinctive shape. But when it is viewed from this standpoint, it can be taken to be the path of natural consciousness which presses forward towards true knowledge, or it can be taken to be the path of the soul as it wanders through the series of the ways it takes shape, as if those shapes were stations laid out for it by its own nature so that it both might purify itself into spirit and, through a complete experience of itself, achieve a cognitive acquaintance of what it is in itself.

We can specify our account of thinking by giving a broad category to the thought-about content. We are concerned with thinking about phenomena, that which appears to us. This adds another difficulty to our analogy to science. How can we think scientifically, that is, systematically, about content so evidently diverse as “things that appear”? If it is propelled by elements external to thinking then our investigation will not be “self-moving”; each step will not be simply implicit in the last. Our guiding metaphor for our investigation will have to be one of “discovery”. But if we are keeping only to the image of a pre-determined space in which we are discovering various objects which pre-exist our discovery, then we have been led back, once again, to our tool image. We are, on this view, “casting the lamp of consciousness” over the dark rooms of phenomena.

Instead, our process should be thought of as one of self-discovery. Everything that we encounter, because we think it, becomes an opportunity to understand the activity of thinking, and, thus, ourselves as thinkers. We are concerned, in short, with how the infinite diversity of appearance helps us to understand ourselves as thinkers. Our systematic investigation will require that we catalog phenomena that demand from us particular forms of response. This catalog of demands will fill out the contours of our capacity to think. And, because our capacities will be provoked by particular phenomena, those capacities will necessarily be linked to them. Our capacities, we will find, are never solely lying in wait (like a tool lying in reserve), but rather intimately linked to these phenomena that are not simply parts of those capacities. It won’t do to speculate about them as a set of instruments “abstracted” from any exercise, since our account of them, and thus our account of thinking as a unified activity, will require always addressing it at the point of expression. Thinking has a “way that it is” only when it is thinking about something. The things thought about are, in turn, understood in their relationship to thinking.

Natural consciousness will prove to be merely the concept of knowledge, that is, prove to be not real knowledge. However, because to a greater degree it immediately takes itself to be real knowledge, this path has a negative meaning for it, and in its eyes the realization of the concept will count to an even greater degree as the loss of itself, for it is on this path that it loses its truth. This path can accordingly be regarded as the path of doubt, or, more properly, as the path of despair, for what transpires on that path is not what is usually understood as doubt, namely, as an undermining of this or that alleged truth which is then followed by the disappearance of the doubt, and which in turn then returns to the former truth in such a way that what is at stake is taken to be exactly what it was in the first place. Rather, the path is the conscious insight into the untruth of phenomenal knowledge, for which the most real is in truth merely the unrealized concept.

We have set our tool image of thinking to one side. But maybe that was (still!) too hasty. After all, the image itself was something we thought, and while we’ve understood what went wrong with it to some extent, we still need to understand how the tool image was something that we thought was so illustrative since it is so common for us to draw upon it. As we go about our systematic investigation to better understand thinking as an activity through the diversity of phenomena, our tool image will reveal itself as more and more limited. But this process will also clarify for us what we meant by the tool image to begin with.

This is because our process will lead us beyond phenomenal things, which appear, to those which don’t: our understanding of our thinking activity will be clarified to us in what about it does not appear. In coming to understand those aspects of thinking which do not appear, a new light will be cast on the phenomena which do. Perhaps most importantly, given the difficulties we ran into with the tool image, our new understanding will intimately relate that which appears to that which does not. And so nothing, in short, will be left behind. It is all thinking, and so greater understanding of it in one dimension leads to greater understanding of it as a unified activity.

Our phenomenal knowledge of things will only be limited in the light of a more complete understanding of thinking, and our knowledge of that limitation, the limit of what there is to know about things that appear, means that we’ll have learned what there is to know about how we think about appearances. We can only know that our knowledge of things that appear is limited, in short, because we understand what’s on the “other” side.

For that reason, this self-consummating skepticism is also not the kind of skepticism with which a fervent zeal for truth and science imagines it has equipped itself so that it might be over and done with the matter. It is not, that is, the resolve in science that one is not to submit oneself to the authority of others’ thoughts, that one examine instead everything for oneself, that one follow only one’s own conviction, or, even better, that one do everything oneself and take one’s own deed alone to be the truth. Rather, the series of its shapes which consciousness runs through on this path is the detailed history of the cultural development of consciousness up to the standpoint of science.

Attempting to understand our scientific activity as paradigmatic for thinking will require us to understand it differently. Rather than focus on the particular matter of an isolated experiment while adopting attitudes we think are appropriate in that context, our investigation will take us far afield to scrutinize the patterns of thinking that enable us long before we enter a laboratory or set up instruments. Scientific thinking is exemplary for us as thinking not because it is ordinary but because it is an achievement in thinking as an activity. And that achievement requires a scaffolding, a bushel of other achievements that provide the background against which scientific thinking makes sense. Science will turn out to be something that we do together.

The former resolve represents cultural development simplistically as a resolution which has been immediately carried out. However, in contrast to that untruth, this path is the actual working out of that resolve. To be sure, following one’s own conviction is more than submitting oneself to authority, but converting opinions which are held on authority into opinions which are held on the basis of one’s own conviction does not necessarily alter the content of those opinions, and it certainly does not thereby replace error with truth. The only difference between abiding by the authority of others or abiding by one’s own convictions in a system of opinions and prejudices lies solely in the vanity inherent in the latter. In contrast, in directing itself to the entire range of phenomenal consciousness, skepticism makes spirit for the first time competent to investigate what is the truth, since it manages to elicit a despair about those so-called natural conceptions, thoughts, and opinions. For this despair, it is a matter of indifference as to whether one calls those conceptions one’s own or ascribes them to others. Consciousness, which straight away gets down to such an examination, is still filled out and burdened with such conceptions and is for that very reason in fact incapable of accomplishing the task which it wishes to undertake.

We are interested in thinking, then, as it has developed. Since what we know about thinking is dependent upon the phenomena that we encounter and the capacities that we demonstrate in those encounters, and what we know about thinking has an effect on our thinking, the story of our thinking has to be a narrative of change. We can only understand how we think if we tell the story of how these encounters informed one another, how our cumulative, transformational understanding of thinking set the stage for the next encounter enabled by what we learned about it in the last encounter.

Furthermore, we’re interested in what we do in thinking. That is, because the book addresses anyone who can read, that means that it does not contain something which only Hegel is capable of thinking. Even the most secret tomes are addressed to us, because they are by their nature public, and so we are interested, always, in how we take them up. The possibility and presence of this we that thinks in common, that is, is capable of the same thinking the same thing, comprises an important element of our understanding of thinking and will play a preeminent role in the argument. Thinking, it will turn out, requires a we, and a we requires thinking.

We are not, however, interested in what we think in the sense of cataloging our ordinary understanding of phenomena. Rather, our approach to thinking begins with our ongoing rejection of the tool model and the shadow that it casts on our ordinary life. Our day-to-day understanding, in short, will have to consistently be supplemented by our recontextualization of it, achieved through systematically laying out its relationships to broader accomplishments in the activity of thinking. What appears obvious will be shown to be able to appear so by virtue of our common activity. And the fact that what is obvious can be so contextualized will prove to be definitive for our scientific understanding of thinking.